Given the state of my body these days you might not believe it, but I’ve climbed Pikes Peak twice.

Two. Whole. Times.

That first trip is the one I really remember. Maybe I blocked out the second? That sounds about right.

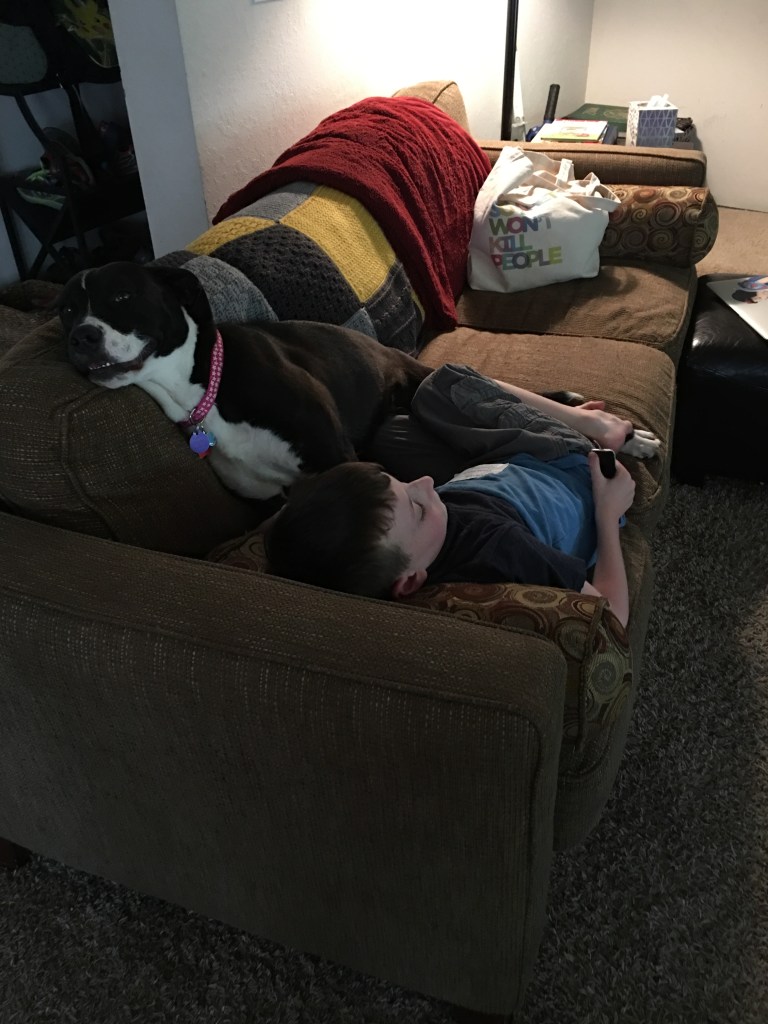

The first climb was with our youth group, and we left early one morning at dawn. Since I was a high school graduate at the time and working for the youth pastor, Rick, as support staff, I went as a volunteer. I can’t remember how many of us went, but I know my 13yo brother, Patton, was there. We were both Pikes Peak virgins. At that point we’d been living in Colorado for just about a year and, after a handful of altitude-induced nosebleeds and some headaches, we had acclimated well to the climate. In fact, we loved it. Somewhere, tucked away in my closet, is a box or two I brought home after our mom died that contain what remains of our childhoods. In it there’s a picture Mom must have snapped of the two of us, sunburned and chapped dry, conked out on the couch together after we got home that evening.

We slept for 16 hours.

If you’ve never done it, the Pikes Peak trail to the peak is a 13.5-mile beast of a climb. Over the course of the 13.5 miles, you gain over 7400 feet in elevation. And in the first six miles you gain over 4000 of those feet. There are lots of tight switchbacks – so it’s not an easy section of the trail, but there’s also a lot of tree coverage in the lower elevation so the added physical drain that comes with sun exposure doesn’t happen until later. I honestly don’t remember struggling at all during that first section. We were told time and again by our youth pastor, Rick, to pack light and carry plenty of water, and back then Patton and I more or less did as we were told, so we were well-prepared and equipped. It also helped that at that time in my life I didn’t have a broken back and was quite fit.

Bless my 18yo heart. I wish I could go back now and tell young Kaysie just how well put together she was at the time. Physically, at least.

Around the 6.5-mile mark on the trail is Barr Camp. The average novice hiker is going to plan to stop here for lunch, and we were no exception. You have to carry in all your own food, and I remember being in great spirits at this point. We all enjoyed hanging out, eating lunch, getting hydrated, and making fun of whatever oddities we managed to find as people passed through.

After lunch, we grabbed our backpacks and continued the hike. Those first couple of miles after Barr Camp are deceiving. It’s the gentlest part of the hike, for sure, which I guess serves the hiker (and the hiker’s digestion system) well right after lunch. But it’s deceiving because you’re past the halfway point and feeling great, and the trail only serves to reinforce your sense that you’ve totally got this. Heck, I may have even told myself that this was easy.

I was wrong.

Once you hit mile three after Barr Camp it quickly becomes crystal clear that this is NOT easy. And there is still a very long way to go. The switchbacks kick in again, and the trees become more sparse the higher you go. At some point, as you approach the A-frame landmark, and the air becomes thinner, you stop joking around and having meaningful conversations with one another, and instead you focus on just breathing and putting one foot in front of the other.

At that point I remember being really glad I had listened to Rick and packed lightly.

That was also the point that one of the younger girls in our group began to whine and complain that her pack was too heavy. We ignored her for a while. But by the time we reached the “Three Miles to the Summit” sign, her whining became less of a whine and more of a complete shutdown. She kept stopping and sitting down – saying she couldn’t go on. But here’s the thing, you can’t stop at that point. And there’s no rescue. In fact, once you start the hike at the crack of dawn, your choices become two-fold – finishing the hike or going back down to the bottom. And at that point (just three miles from the summit), going back down would be harder and take longer than finishing those final three miles. We couldn’t let her stop. We pushed her. We kept pushing her. We took turns pushing her – one of us staying with her the whole time.

Finally, in an act of desperation, she threw down her pack and collapsed to the ground.

At this point, I was pissed. I was exhausted. I needed to expend 100% of my available energy (which wasn’t much) trying to get myself to the top and now here was this girl who was taking from the little I had available. In my frustration, I grabbed her pack, intending to shove it on her back myself… and suddenly realized the problem.

This kid was carrying everything she owned in that backpack. I couldn’t believe how heavy it was.

“What did you pack in here?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” she replied through her sobs… “water, food, a change of clothes, extra shoes, make up, a brush, a mirror, a flashlight…” and on and on she went.

I may have spontaneously combusted in that moment.

Rick and I pulled away to debate over what we should do. I suggested we toss the pack on the side of the trail because she certainly wasn’t going anywhere with that pack on her back. But in the mountains the “Leave No Trace Behind” rule is sacrosanct. Leaving it behind wasn’t an option. And leaving her behind was also not an option (although that seemed like a solid choice to me). So instead, we agreed to take turns carrying her pack.

I’m pretty sure hiking those last three miles was the hardest physical thing I’ve ever done. And I’ve had four babies – three of them birthed naturally with no pain medications and extremely long labors. Okay, so maybe giving birth was harder, but there was the reward of an actual new human life at the end, so let’s say hiking those last three miles was the second hardest physical thing I’ve ever done.

For the remainder of the long and HARD hike, not only were we carrying her ridiculously heavy backpack as well as our own, we were literally pushing that kid up to the summit.

While she cried.

I had to dig down deep to find the strength to keep climbing, but I had to dig down even deeper to find enough Jesus in me to keep from strangling that girl. She was a heavyweight that we didn’t ask for and I can’t say that I carried her with a lot of grace that day. In fact, when we reached the top of Pikes Peak, while everyone was celebrating and clapping each other on the back, I struggled to join in. It took me some time to get over my frustration with that kid.

I also had to run to the bathroom and throw up, so there was that.

In general, I don’t carry things lightly.

I mean, I think I used to (except for heavy backpack girl).

Or maybe I was at one time less aware of the amount of weight I carried. Or maybe I once had the capacity to carry heavy things lightly, but don’t have as much capacity now.

It’s something I’d like to change, and I spend a lot of time thinking about how to do so while still being honest about feeling weighed down.

That’s the tricky part – honesty and surrender all at the same time.

My mom managed it. There are literally hundreds and maybe even thousands of people who crossed paths with my mom, felt the warmth of her presence and the strength of her faith – never knowing that she was wife to an alcoholic/drug-addicted man who was sucking the very life from her veins while she worked herself to the bone to support him. And there were at least that many people who did know of the suffering she endured at the hands of my father and that knowing increased their felt sense of being strengthened by the seemingly unlimited well of faith within her.

Years later, when her body was riddled with cancer and she lay in the hospital, anyone who cared for her or came to visit her experienced the grace with which she suffered. She remained kind and loving and confident that Jesus was with her and would save her.

Spoiler alert: He didn’t.

But here’s the thing – in the wee hours of the nights I sat beside her hospital bed when she was sick; and in the 40 years of living with and supporting my father as we were manipulated and berated and abused by him; and in the last few days she was here on earth – suffering and resisting the morphine we offered her knowing it would ease her pain but also disconnect her from the people she loved…

She let me see the truth.

I saw the fear. I saw the hopelessness. I saw the doubt. I saw the desperation.

She carried a heavyweight.

There were even times when she was “heavy backpack girl” and I had to carry her pack for her while pushing her towards the summit. Actually, there were a lot of those times.

And, unlike with the kid on the mountain, I felt honored to be her person for so many years. She was the kind of person you wanted to be close to, the kind of person you wanted to be needed by, the kind of person who radiated light and joy despite her situation.

I didn’t realize until after she was gone that it’s hard to absorb someone’s light and joy when you’re exhausted from the work of helping them reach the summit.

Her joy didn’t become mine. She modeled it beautifully, but it wasn’t some inheritance I was entitled to.

And I didn’t realize until she was gone that she was a heavyweight. Not always. But sometimes.

I don’t mean to dishonor her with this confession. All of the wonderful things about her – and there were so, so many – are still true. And they did make my life better. But this is exactly my point. The things that are beautiful about us can coexist with the things that are really, really heavy and hard. Our culture doesn’t do a great job at this kind of cohabitation. The church certainly struggles with it. But not just the church. Everyone.

And the truth is that some people don’t carry heavyweights. (God bless those of you in this category, but you are not my people.) And some of those who do carry a heavyweight – maybe those who have wrestled it out, gone to therapy and done some inner work – have a better grasp on how to carry heavy things while maintaining an inner lightness while also being honest about how hard it actually is. (God bless those of you in this category. You are my heroes.) And maybe others of us who carry heavyweights are only able to do all those nice things after the heavyweight has been lifted. (God bless those of you in this category. Thanks for not leaving me here alone.)

And there’s the rub for me. My heavyweight isn’t going anywhere. It’s multi-faceted – chronic pain, grief and loss, chronic depression and anxiety, financial woes, physical limitations, complex family challenges – and reaching the summit feels impossible, at least in this lifetime. It’s hard to know that the climb – with its exhaustion, steep inclines, weather variations, and so many more hard things – won’t be done until I’m done with life on this earth.

But even though I don’t carry things lightly, I do keep climbing. I keep putting one foot in front of the other, sometimes ugly crying and often complaining, while Jesus offers to carry my overloaded backpack (and I struggle to give it to Him because for whatever reason I’ve packed all my precious things in there and don’t want to let them go) and even push me step after step towards the summit.

I’m grateful for His help, for His presence with me as I climb. And I wish it wasn’t so damn hard. And I’m exhausted. All of these are true.

Hopefully, one day, when I finally get to the peak of the mountain, He’ll celebrate freely with me despite what it cost Him to get me there.

And I’ll finally put that heavyweight down.